It took me some time to decide to write. Somewhere along the way, I believed that writing was meant for curators, art historians, or collectors, not for artists themselves. Yet I felt the need to create a space for it anyway. Not to explain my work but to share what shaped it : the thoughts, the references, the process that has held me together, from drawings to collage films, and to AI. Not full manifestos necessarily, only perspectives where I can go deeper than with a social media caption. So here we are. A first letter, I hope you’ll enjoy it, and that it will generate some insightful interactions with some of you (artists, curators, collectors, journalists).

A First Letter About a First Contact

In 2022, after some time working with archival video collage, I began experimenting with AI image generation, more as a curiosity than as a clear artistic direction.

These early explorations became a series of memory-like photographs that I later gathered into the video triptych titled I can’t remember, shown in March 2023 at the NFT Factory as part of the group show 100% AI – That Doesn’t Exist.

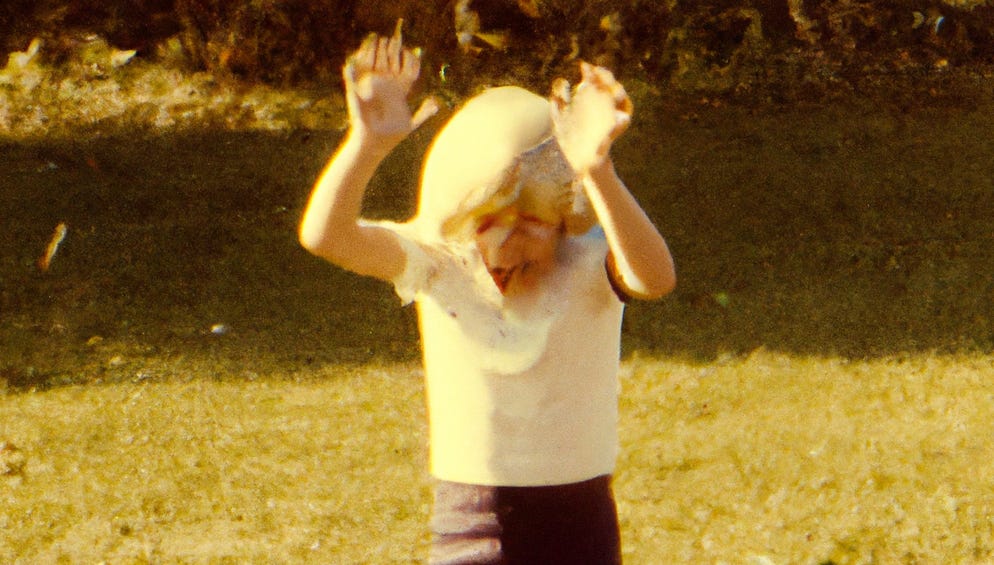

The generated images with DALL·E looked like fragments from a memory archive, suspended somewhere between the 1950s and the 1990s: imagined family gatherings, garden walks, quiet parties. Red faces, blurred smiles, leftover food, and wet sidewalks. The original images are now being minted in the collection I wasn’t there, on objkt.

The video was introduced with a simple line: “This is a story I can’t remember. I can’t remember the names, or what exactly happened. But I remember the feelings, and a few scattered details. There was joy, sweetness, laughter, death, and decay.” The soundtrack was built from fragments of the 1970s documentary The Mind-Benders: LSD and the Hallucinogens, about the history, risks, and potential of psychedelics. The voices felt oddly right. Unstable, searching.

I was trying to reimagine what my own family might have looked like before I was born, or at a time when I was too young to remember. What emerged was an AI version of white Western middle-class life. Comfortable, expressive, privileged. A world that felt warm and familiar, and unaware of itself. Appearing safe, while being quietly shaped by dominant structures I could not yet name.

The people in these images seemed capable of love, vulnerability, and genuine care. Some moments felt tender and intimate. Others, strangely bitter. The nights were loose and uncontained. The sunlight on their faces, almost totalitarian.

And Then the Dead Hare Became Visible

If you watch the video, you might notice a few brutal images standing out. A rotten apple. A hare. A bird. Both animals dead, their bodies decaying somewhere in the frame. Friends asked me about this: why introduce such morbid violence into what feels like a dreamy, nostalgic bubble?

The reason felt instinctively clear, but difficult to explain. In this very uncanny archive, something important was needed.

That something … was a kind of a sacrifice. A visual sacrifice of a being was needed, in order for the memory to feel whole and real.

But it wasn't the real answer, and I needed to go deeper than that. Oddly enough I found it … in still life paintings.

I didn’t realize it at first, but since childhood, I’ve always felt a deep pull toward still life. Something unsettling in the arrangement of objects and animals. Not to tell a story, but to display presence, to stage a moment of offering, ceremonial suspension... and control.

The precision of it captivated me. The skin of fruit, the folds of fabric, the shimmer of metal, the slack limbs of hunted animals, as if in worship. These weren’t just moralistic images of abundance, to me, they were images of power, possession.

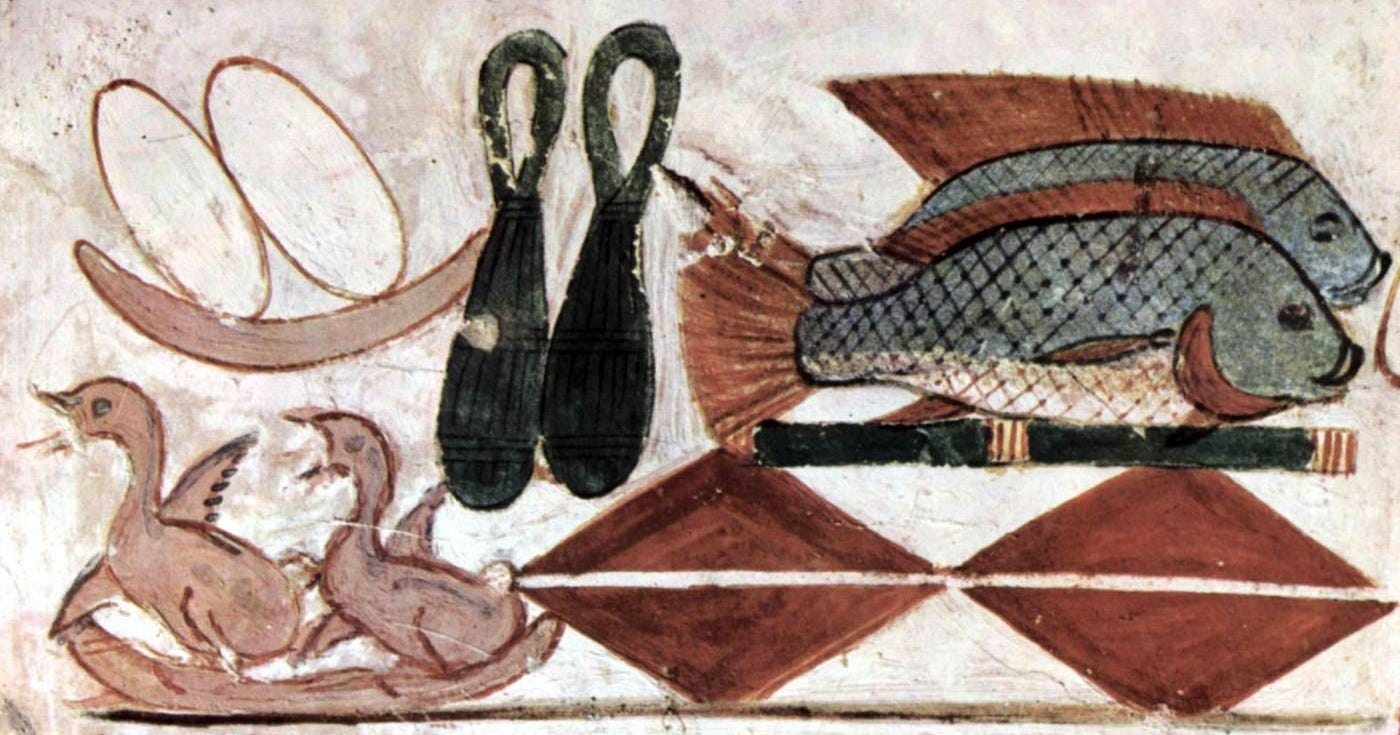

And sacrifice. I think still life has always been about it. In Egyptian tomb paintings, food, flowers, and animals were not symbolic; they were literal gifts, “killed” and magically preserved to serve the needs of the dead. A quiet ritual designed to make him feel safe, content, and in control. Even in European still life painting, I sense that this sacrificial logic endured. Whether Christian or pagan, the gesture never disappeared.

It is of no consequence if, in the process, the reality of the still life as part of an actual world is sacrificed, and indeed that sacrifice is necessary if painting is to move from representation to presentation, from a stage of transcribing reality to a stage where the image seems more radiant, more engaging, and in every way superior to the original- which the painting can dispense with.

Norman Bryson, Looking at the Overlooked: Four Essays on Still Life Painting (1990)

To me, this was not just an aesthetic tradition. It was a system of visual domination in which violence is ritualised, refined, and made beautiful.

Coming back to the AI-generated pictures, it took me time to realize that this aesthetic fascination was personal. I had grown up surrounded by warmth, safety, and comfort, but as a kid, I slowly began to understand what made that possible.

The clothes we wore, the food we ate, the sense of security we felt, the entertainment we consumed, the technology we bought. All of it was made possible by the labor and lives of others. Other people. Other animals. Other countries, made invisible.

What had seemed natural or deserved was the result of a system built on the erosion of others’ lives. A life built on energy, risk, and sacrifice, ritualised by politics, racism, and mysoginy.

A very naïve, basic statement, you would say (and I agree), but a deeply primal lesson when you grow up. Still life, somehow, helped me to make the ritual visible.

So yes, the dead animals had to be there. Their presence gave these AI memories weight, texture, and blood, and oddly enough, tenderness. They made them believable.

A First Attempt to Remember

The project became a speculative album of my parents’ and grandparents’ lives. The result is very subjective, probably judgmental.

And it wouldn’t be the last time I turned to memory as a theme. The more I worked with AI, the more I found myself drawn to the ways memory functions, not as something fixed, but as something extremely shifting. Shaped by the present, by emotion, by cultural codes, and by media.

With a background in art history and an interest in psychology, I began reading works by Francis Eustache, Marianne Hirsch, Yvon Lemay, among others. I wanted to understand how something so essential to our identity, could feel so fragile, and easily manipulated.

A memory that doesn’t record, but rewrites. That doesn’t preserve, but performs. Breathing, fragmenting, reforming over time, and, in a way, always contemporary.

“…we now know that we do not record our experiences the way a camera records them. Our memories work differently. We extract key elements from our experiences and store them. We then recreate or reconstruct our experiences rather than retrieve copies of them. Sometimes, in the process of reconstructing we add on feelings, beliefs, or even knowledge we obtained after the experience. In other words, we bias our memories of the past by attributing to them emotions or knowledge we acquired after the event.”

Daniel L. Schacter in The Seven Sins of Memory (2001)

It made sense that contemporary art would be drawn to this, as it has been for as long as it’s existed. And AI, with all its ambiguity, would obviously join the conversation.

I came across amazing artists with the same interrogations and perspectives: u2p050, Mind Wank, Maria Mavropoulou and others... And discovered the academic journal Memory, Mind and Media, and in particular the paper Shall the robots remember? by Mykola Makhortykh, a deeper look at how non-human communication agents shape collective memory.

I am relieved and happy to find comrades in this visual exploration.

Conclusion: A Box of Memory Somewhere

In 2025, I began minting the series I wasn’t there, on objkt. As with all my work, I wanted each piece to remain unique. Many of the images are still waiting to be minted.

This collection became, for me, a kind of final album, not a closure, but a container that holds a double nostalgia: one for a past I barely experienced, and one for that first intimate encounter with AI in my life. Both are distant and personal.

I’m looking forward to sharing more, and to the quiet conversations this might open with anyone drawn to these questions.

With care,

Marine